If you’ve used an AI coding agent for more than a few hours, you know the “wall”: the agent makes visible progress, then stalls — and you end up patching and finishing the work yourself.

As AI engineers are often wont to do, a pattern emerged to solve that problem: just loop the agent against external checks until the job actually passes.

The approach caught on hard enough that it got a name — Ralph Wiggum.

And the meme stuck because the pattern works. By late 2025, Anthropic had formalized it into an official Claude Code plugin.

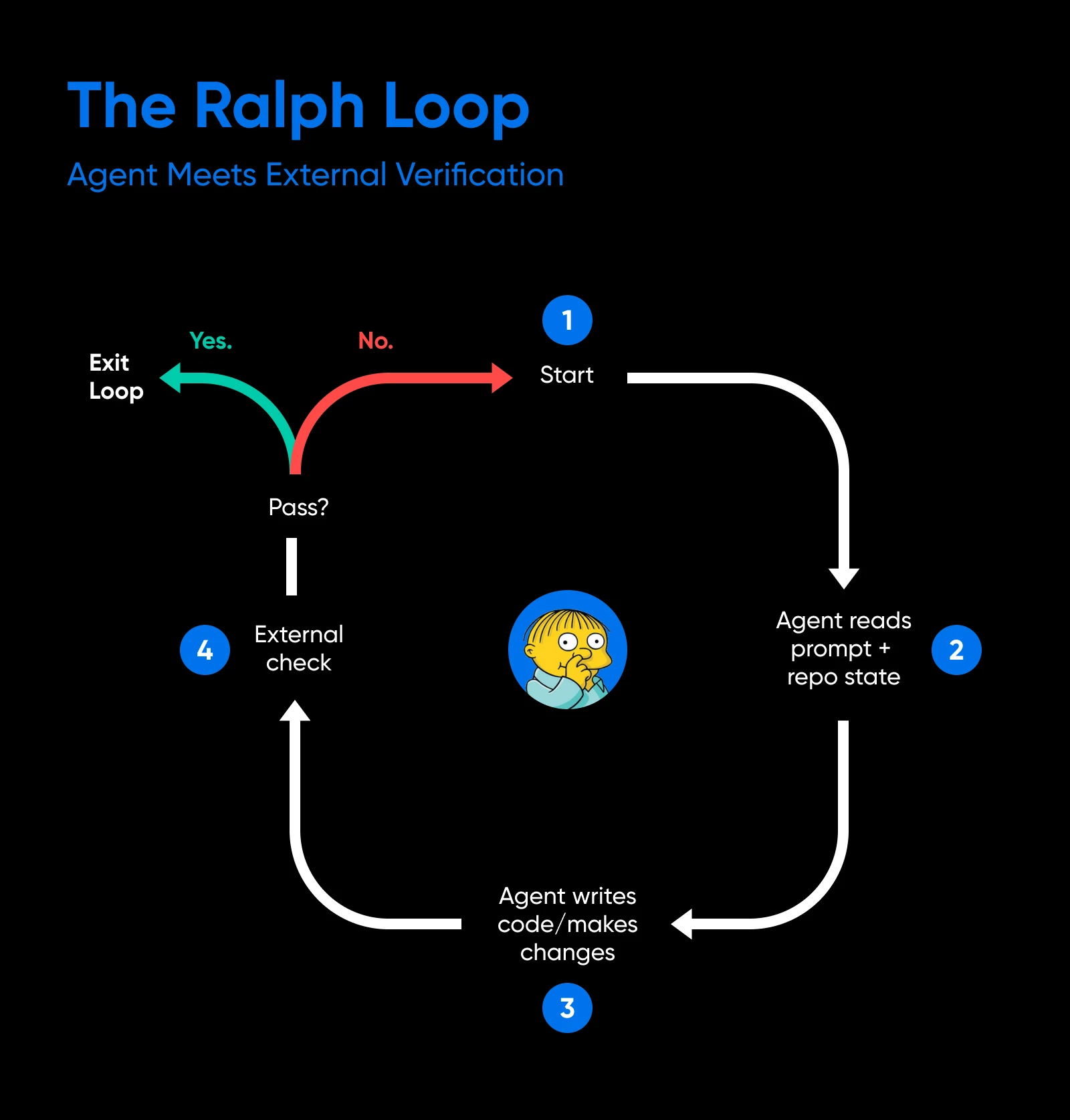

Ralph represents a shift in how developers are using existing tools. Instead of treating AI systems as interactive assistants, they’re being run as long-lived processes, guided by tests, linters, and explicit stop conditions.

So this short guide is the practical version. We’ll see what Ralph actually is, why it works, how it spread, and what changed when it was productized.

What Is “Ralph,” Really?

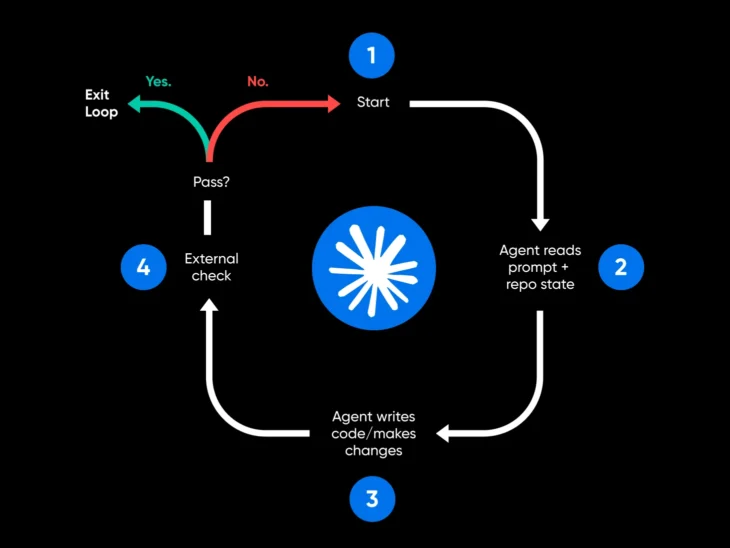

At its core, this is what Ralph is: run an agent in a loop, check the output against something that can’t lie like a test, a linter, a type checker; and keep looping until it passes.

That’s it.

The original example Geoffrey Huntley shared in July 2025 was intentionally blunt:

while :; do cat PROMPT.md | npx --yes @sourcegraph/amp ; doneClaude Code variants follow the same shape, just with more guardrails. But the principle doesn’t change: feed a pinned prompt into the agent repeatedly until external reality says you’re done.

The loop itself is almost irrelevant, and what matters is the contract:

- State lives in the repo: Files, diffs, logs, git history; anything durable goes here.

- Completion lives outside the model: Tests, linters, type checkers; the agent doesn’t decide when it’s finished; the harness does.

- The agent is replaceable: It’s a worker invoked repeatedly until the gate passes; if it’s slow or dumb today, swap it for something faster tomorrow.

Seen this way, Ralph becomes a design principle: stop asking the model to know when it’s done. Stop expecting it to remember constraints across context resets.

Instead, build the system so the model can’t fail in those ways.

Why Does the Loop Hold Up?

A few reasons:

1. Context Windows Behave Like Buffers

Huntley often frames context windows in low‑level terms:

“Think like a C or C++ engineer. Context windows are arrays.”

They have a fixed size; they slide; they overwrite; they forget.

Long-running sessions assume continuity that doesn’t exist, so treating the buffer as durable memory leads to drift, missed constraints, and inconsistent behavior.

Ralph leans into the reality of the system. Rather than pretending the context window is stable, it treats it as disposable.

The agent’s scratch space is reset between iterations, while the durable state persists on disk. The repo accumulates truth across runs. This makes restarting the agent routine rather than wasteful; each loop starts fresh but builds on what actually persisted.

2. External Checks Outperform Internal Reasoning

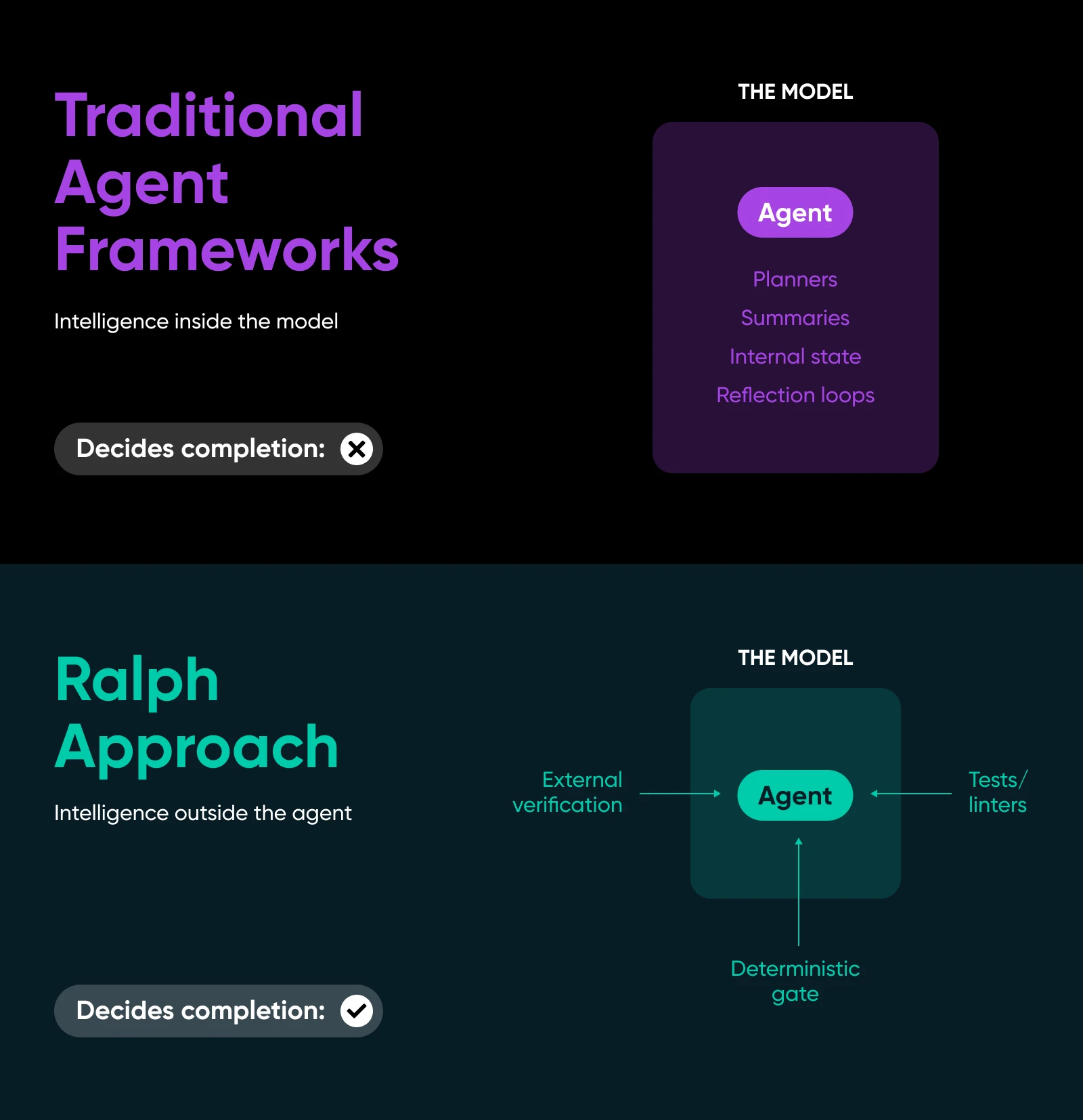

Many agent frameworks respond to failure by adding structure inside the model: planners, summaries, internal state, and reflection loops.

Ralph keeps the intelligence outside the agent. It relies on:

- A pinned spec that does not drift

- Concrete evidence from the last run

- A deterministic gate that evaluates success

The agent does not decide when work is finished – the harness does.

This is why Ralph excels at mechanical work: refactors, migrations, cleanup, conformance tasks… Anywhere success can be measured by a script rather than judgment, iteration becomes reliable.

The model can’t wiggle out of the requirements because the requirements live outside its reasoning.

3. Compaction Erodes Constraints

One recurring critique from Huntley targets summarization and compaction.

When a system asks the model to decide what matters enough to keep, information is lost — constraints soften, edge cases disappear, and pins fall out.

Ralph sidesteps this by keeping inputs literal:

- The specs stay verbatim instead of getting summarized,

- The failure output remains raw and unfiltered; and

- Memory curation never moves into the model.

The harness preserves fidelity; the agent operates inside it, constrained by what’s actually there rather than what the model thinks should be there.

So, How Did the Idea Spread?

The timeline is pretty compressed.

- June 19, 2025: At a San Francisco meetup of about 15 engineers discussing agentic coding, Huntley demos Ralph, Cursed (the programming language being built by Ralph), and livestreams autonomous coding overnight while asleep in Australia. The room has an unsettling conversation about how easy it is to copy 80%-90% of a SaaS and how many types of work are about to disappear entirely.

- July 2025: Huntley publishes the original blog post with the basic bash loop structure. The piece includes a lightweight example prompt and an ask: “you could probably find the cursed lang repo on github if you looked for it, but please don’t share it yet.”

- August 2025: The YC agents hackathon happens — teams run Claude Code in continuous loops. The result is 6 repositories shipped overnight. Dexter Horthy runs an experimental Ralph loop on a React codebase refactor. Over 6 hours, it develops a complete refactor plan and executes it.

- September 2025: Huntley launches Cursed Lang officially, the programming language that Ralph built. It exists in three implementations (C, Rust, Zig), has a standard library, and a stage-2 compiler written in Cursed itself.

- October 2025: Dexter presents Ralph at Claude Code Anonymous in San Francisco. The question from the audience: “So do you recommend this?” His answer: “Dumb things can work surprisingly well. What could we expect from a smart version?”

- December 2025: Anthropic releases an official Ralph Wiggum plugin. The plugin takes Huntley’s bash loop and formalizes it with Stop Hooks and structured failure data.

- January 2026: Huntley and Horthy do a deep dive YouTube discussion comparing the original bash-loop Ralph implementation with the Anthropic stop-hook implementation.

Bash-loop Ralph vs. Plugin Ralph

The original Ralph is a 5-line bash loop. You cat a prompt file, pipe it to Claude, check if the output passes your test, and loop until it does. Everything lives on disk, everything is visible. If something breaks, you can see exactly why.

The Anthropic plugin inverts that model, so instead of running the loop from outside, it installs a Stop Hook inside your Claude session. When Claude tries to exit, the hook intercepts it, checks your completion conditions, and feeds the same prompt back in if work remains. The files Claude modified are still there.

The git history is still there, but the harness mechanics are now opaque — hidden in a markdown state file, sensitive to permissions, easy to break if you don’t know what you’re doing.

This is the classic abstraction tradeoff.

The plugin lowers adoption cost. You don’t need to write bash and you don’t need to think about loops. But as the mechanism gets hidden, the original insight gets easier to miss.

The bash-loop version forces you to design the harness. The plugin version lets you skip that step, which is fine until you hit an edge case and can’t see what’s actually happening.

Dexter Horthy tested it and found it dies in cryptic ways unless you use “–dangerously-skip-permissions.” The plugin installs hooks in weird places, uses opaque state files, and if you delete the markdown file before stopping it, you break Claude in that repo until you disable the plugin entirely.

So, what’s the lesson? Both work, but they work for different reasons. The bash loop works because it’s dumb and transparent. The plugin works when the abstraction doesn’t hide something critical.

What Do You Learn from Running It?

Ralph assumes distance between the human and the agent. You don’t sit in the session and guide it. Instead, you set it running, walk away, inspect the artifacts when it finishes, and adjust the constraints for the next iteration.

Interaction happens at the harness level — the prompt, the tests, the stopping conditions — not inside the conversation.

Over time, a pattern emerges: most failures aren’t model failures; they’re harness failures.

The spec was vague, the test was too broad, or the completion condition didn’t actually describe what “done” means.

Once you see this a few times, your instinct shifts. You stop asking “how do I make Claude smarter?” and start asking “how do I make the constraints tighter?”

This is where specs become critical.

Specs as Control Surfaces

Huntley reframes specs not as documentation but as fixed control inputs. You produce them through conversation with Claude, edit them deliberately until they’re precise, and then pin them. Once pinned, they don’t change for the entire loop.

This matters because specs do three things at once:

- They bind what the agent can invent: Without a tight spec, Claude will add defensive layers, abstractions, or features you never asked for, expanding scope with every iteration.

- They anchor search and retrieval: So the agent doesn’t hallucinate new requirements.

- They stabilize behavior across runs: Each iteration is solving the same problem, not a slightly different interpretation of it.

If your spec is vague about what “done” means, the agent will interpret it differently each loop. You end up with drift, scope creep, and iterations that contradict each other.

How Do You Run the Loop Responsibly?

A minimal Ralph setup often looks like:

MAX_ITERS=30

for i in $(seq 1 $MAX_ITERS); do

cat PROMPT.md | claude

if ./ci.sh; then exit 0; fi

done

exit 1The mechanics of the loop matter far less than the rules around it:

- Keep the spec immutable; don’t adjust it mid-loop based on what Claude is doing.

- Encode completion as executable checks.

- Enforce iteration limits and time limits so the loop can’t run forever and burn through your token budget.

- Preserve logs and diffs so you can inspect what went wrong if it does.

Further, operational practice has revealed a few heuristics that matter:

- Prefer small, regular diffs over large refactors, because large changes compound errors and are harder to debug.

- Rerun on current main rather than rebasing, because merge conflicts waste iterations.

- And avoid using Ralph for exploratory work, because if you don’t have clear acceptance tests, you’ll just get a chaotic loop that invents things you didn’t ask for.

The constraint is the feature.

The Loop Is the Lesson

As Ralph gained traction, variations emerged. Some teams built structured outer loops around tool-calling agents. Others added separate verifier components: a different model that reviews the worker’s output before the loop decides to exit. These extensions work, yes, but only if they respect the original insight.

The rule is simple: verification must stay deterministic, and summaries must never replace primary inputs.

- If you add a verifier, it should check concrete things: tests pass, linter exits cleanly, git diff matches expectations.

- If you add structured outer loops, they should still see the raw output and raw logs, not a cleaned-up summary of what went wrong.

Huntley’s core argument is that software development as a profession is effectively dead, but software engineering — the practice of building systems well — is more alive than ever.